It’s December 2020, and only now, in retrospect, do I feel able to properly reflect on the beauty and learnings from the trip to Calabria that happened exactly one year ago. Bergamot harvest in Italy falls between November and February. Last year, Christophe Laudamiel invited a small group of friends and colleagues to visit the world’s leading bergamot producer based in Reggio Calabria, at the southernmost tip of Italy.

As soon as we flew home, the first rumours of a deadly pandemic reached us back in the UK. Our year since then exists inside a Mad magazine back page fold; the picture that it reveals, a grotesque monster.

You’ll understand why on return, instead of reflecting on the goosebump-inducing sensory pleasure of eating bergamot sorbet at night while watching Christmas lights twinkle on the sea between us and the island of Sicily, I followed in horror as news reports started pouring in.

Now, with a vaccine in sight, there is once again hope. And I can’t think of a better ingredient to focus on than bergamot when the whole needs a sedative [1].

Capua in Calabria

Bergamots are almost exclusively grown in southern Italy, especially in Calabria, over approximately 1,400 hectares of dedicated land. Italian migrants took bergamot trees with them to America, and there has also been some bergamot activity on the Ivory Coast, but it’s safe to say most of the world’s bergamot comes from the Calabria region.

The leading supplier there is a five-generation family business, named Capua 1880 from the family name and its founding year.

Laudamiel assembled a small group of people with eclectic but relevant backgrounds: a team from a Japanese pharmaceutical and cosmetics company; two young perfumers; a frankincense distiller from Oman; owner of an Amsterdam perfume store – and us (Pia and Nick from Olfiction).

Our host Laurent Bert (international sales director) came to meet us on the morning of the first day, with a full printed schedule for our three days: tour of all the citrus processing facilities including the factory floor, storage areas, R&D lab and high-tech unit where fractions, decolourisation and other technical processing happens; a tour of one of the citrus fields; half a day spent at head office smelling and learning about all the different oil qualities. Plus, of course, dinners, during one of which we diverged quite a bit into smelling some vintage and current perfume samples Christophe had brought with him.

And I may be banal, but I am still wistful about starting each day with a proper Italian coffee.

Bergamot processing

Bergamot is a hybrid fruit that originated from a base rootstock of a bitter orange tree grafted with a branch from a lemon tree. After all these years of using bergamot oil in my work, I must admit that bergamot being a hybrid tree was news to me. Of course, nowadays bergamot branches can be used themselves when there’s an established field – as there are plenty of mature trees.

The tree produces fruit after 3 years, which are collected by hand. The fruit softens for a few days in the factory, in big piles of crates. There are two initial processing methods.

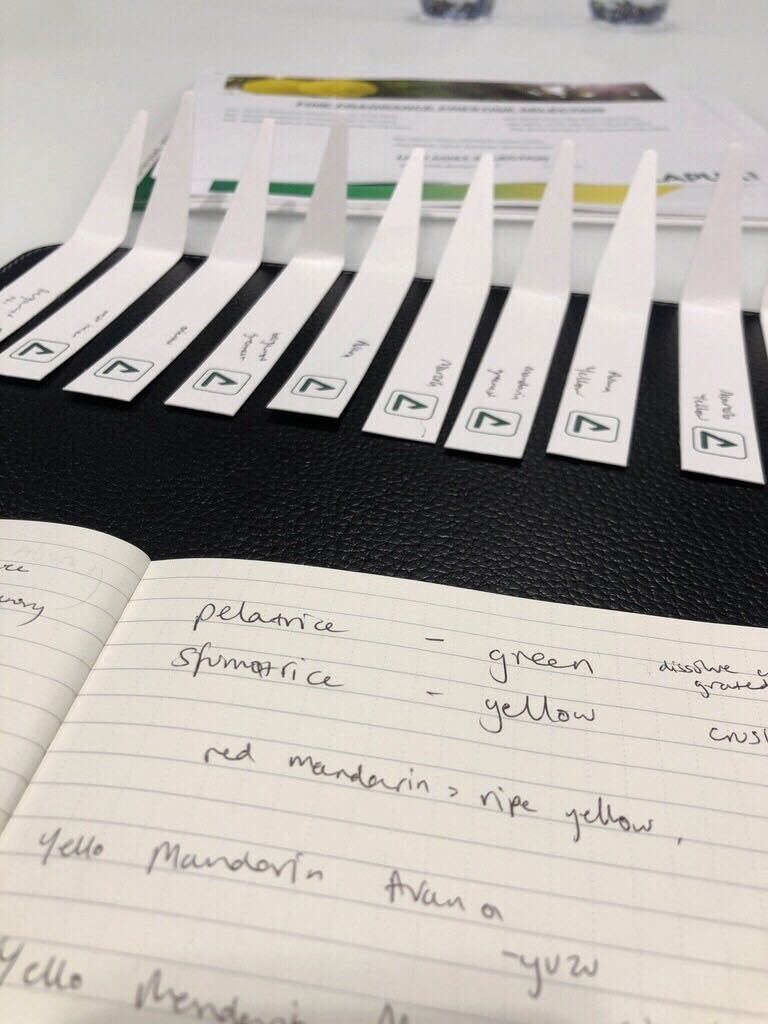

The pelatrice process involves fruits loaded into a “pelatrice” which moves the fruit into a rotating drum. Water is sprayed inside the drum while the drum itself grates the skin of the fruit, and the fruit is kept watered throughout. This forms an emulsion of essential oil, water, and rind residue. The emulsion is cleared of residue through vibration, and the leftover skin collects separately from the essential oil and water emulsion. The emulsion goes through a centrifuge which removes 85% of the water, before passing through a finisher which strips the remaining water and leaves only the essential oil.

The sfumatrice process involves two horizontal ribbed rollers through which the citrus peels are pressed to release their oil. The oil is washed away with fine water spray, and then goes through a separator before being purified by a centrifuge.

These two methods result in a different end product, which can then be further “cleaned”, fractionated or decolourised. Indeed, Capua has an entire site dedicated to additional technologies like molecular stripping. We were able to follow all of the processes first hand, and smell the output in situ to compare and contrast.

The sensory delight of bergamot

In fact, one of the things we were able to try fresh from the process, was bergamot juice, freshly squeezed. I expected it to be very bitter (and it was), but I had not expected the peppery effect – so peppery that it was almost dancing around like popping candy on my tongue. This is one of those annoying things to consider: yes, it’s a privilege to go on buying trips, and alas, they do really add a whole new dimension to the appreciation of a raw material. I have immediately put the new dimensions of bergamot that I discovered on this trip to use at work.

Bergamot essential oil is used in the vast majority of fine fragrances; it is so ubiquitous that calling it your favourite perfumery ingredient is like saying that pasta is your favourite ingredient in Italian cooking. Nevertheless, bergamot is probably my favourite ingredient (especially after this trip).

Bergamot was famously overdosed in Shalimar (to help balance the extreme sweetness). It is a fundamental ingredient in eau de colognes, and can bring lift and freshness to almost any type of fragrance. The secret to its wonderful abilities to act as a top note and a harmoniser is its chemical composition – touching both floral and citrus facets.

During the day that we smelled through lots of bergamot and other citrus varieties at Capua HQ, we explored different qualities and fractions, while discussing their potential uses in perfumery; problems they might solve and so on. Talk turned to the possibility of novel citrus ingredients – one of Laudamiel’s driving forces is to try new things and to bring rarer materials onto his palette. The realities of that approach sometimes make it unviable for businesses due to the simple fact of operational sense: why diversify to a niche material when those same business resources could be used to produce something that already has an established and guaranteed market. Nevertheless, who knows – the answer may not even necessarily be a new plant variety, but instead, new processing and post-processing methods; there is potential for creativity and novelty in a marriage of nature and science, as perfumery has shown us from the very beginning.

Olfiction perfumer Pia Long smelling an orange flower in Calabria

View from out hotel

[1] anecdotally, bergamot oil seems to have a sedative and cheering effect on people, and has been used in aromatherapy for uplifting and anti-anxiety blends for this reason. Some modern studies now back this folklore, such as the pilot study published in May 2017 issue of Phytotherapy research that examined the effect of bergamot oil inhalation on participants of mental health clinical trials – and found a 17% improvement in positive feelings versus the control group: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ptr.5806